A

computer is a general purpose device that can be programmed

to carry out a set of arithmetic or logical operations. Since a

sequence of operations can be readily changed, the computer can solve

more than one kind of problem.

Conventionally, a computer consists of at least one processing element, typically a central processing unit (CPU) and some form of memory.

The processing element carries out arithmetic and logic operations, and

a sequencing and control unit that can change the order of operations

based on stored information. Peripheral devices allow information to be

retrieved from an external source, and the result of operations saved

and retrieved.

The first electronic digital

computers were developed between 1940 and 1945. Originally they were

the size of a large room, consuming as much power as several hundred

modern personal computers (PCs).

[1] In this era mechanical analog computers were used for military applications.

Modern computers based on integrated circuits are millions to billions of times more capable than the early machines, and occupy a fraction of the space.

[2] Simple computers are small enough to fit into mobile devices, and mobile computers can be powered by small batteries. Personal computers in their various forms are icons of the Information Age and are what most people think of as “computers.” However, the embedded computers found in many devices from MP3 players to fighter aircraft and from toys to industrial robots are the most numerous.

History of computing

Etymology

The first recorded use of the word “computer” was in 1613 in a book

called “The yong mans gleanings” by English writer Richard Braithwait

I

haue read the truest computer of Times, and the best Arithmetician that

euer breathed, and he reduceth thy dayes into a short number. It

referred to a person who carried out calculations, or computations, and

the word continued with the same meaning until the middle of the 20th

century. From the end of the 19th century the word began to take on its

more familiar meaning, a machine that carries out computations.

[3]

Mechanical aids to computing

The history of the modern computer begins with two separate

technologies, automated calculation and programmability. However no

single device can be identified as the earliest computer, partly because

of the inconsistent application of that term

[4]. A few precusors are worth mentioning though, like some

mechanical aids to computing, which were very successful and survived for centuries until the advent of the electronic calculator, like the Sumerian abacus, designed around 2500 BC

[5] of which a descendant won a speed competition against a contemporary desk calculating machine in Japan in 1946,

[6] the slide rules, invented in the 1620s, which were carried on five Apollo space missions, including to the moon

[7] and arguably the astrolabe and the Antikythera mechanism, an ancient astronomical analog computer built by the Greeks around 80 BC.

[8] The Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria

(c. 10–70 AD) built a mechanical theater which performed a play lasting

10 minutes and was operated by a complex system of ropes and drums that

might be considered to be a means of deciding which parts of the

mechanism performed which actions and when.

[9] This is the essence of programmability.

Mechanical calculators and programmable looms

Blaise Pascal invented the mechanical calculator in 1642,

[10] known as Pascal's calculator, it was the first machine to better human performance of arithmetical computations

[11] and would turn out to be the only functional mechanical calculator in the 17th century.

[12] Two hundred years later, in 1851, Thomas de Colmar released, after thirty years of development, his simplified arithmometer;

it became the first machine to be commercialized because it was strong

enough and reliable enough to be used daily in an office environment.

The mechanical calculator was at the root of the development of

computers in two separate ways. Initially, it was in trying to develop

more powerful and more flexible calculators

[13] that the computer was first theorized by Charles Babbage

[14][15] and then developed.

[16] Secondly, development of a low-cost electronic calculator, successor to the mechanical calculator, resulted in the development by Intel

[17] of the first commercially available microprocessor integrated circuit.

In 1801, Joseph Marie Jacquard made an improvement to the textile loom by introducing a series of punched paper cards

as a template which allowed his loom to weave intricate patterns

automatically. The resulting Jacquard loom was an important step in the

development of computers because the use of punched cards to define

woven patterns can be viewed as an early, albeit limited, form of

programmability.

First use of punched paper cards in computing

The Most Famous Image in the Early History of Computing[18]

This portrait of Jacquard was woven in silk on a Jacquard loom and

required 24,000 punched cards to create (1839). It was only produced to

order. Charles Babbage started exhibiting this portrait in 1840 to explain how his analytical engine would work.

[19]

It was the fusion of automatic calculation with programmability that produced the first recognizable computers. In 1837, Charles Babbage was the first to conceptualize and design a fully programmable mechanical computer, his analytical engine.

[20]

Limited finances and Babbage's inability to resist tinkering with the

design meant that the device was never completed—nevertheless his son,

Henry Babbage, completed a simplified version of the analytical engine's

computing unit (the

mill) in 1888. He gave a successful demonstration of its use in computing tables in 1906. This machine was given to the Science museum in South Kensington in 1910.

Ada Lovelace, considered to be the first computer programmer

[21]

Between 1842 and 1843, Ada Lovelace, an analyst of Charles Babbage's analytical engine, translated an article by Italian military engineer Luigi Menabrea

on the engine, which she supplemented with an elaborate set of notes of

her own. These notes contained what is considered the first computer

program – that is, an algorithm encoded for processing by a machine. She

also stated: “We may say most aptly, that the Analytical Engine weaves

algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and

leaves.”; furthermore she developed a vision on the capability of

computers to go beyond mere calculating or number-crunching

[22]

claiming that: should “...the fundamental relations of pitched sounds

in the science of harmony and of musical composition...” be susceptible

“...of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism

of the engine...” it “...might compose elaborate and scientific pieces

of music of any degree of complexity or extent”.

[23]

In the late 1880s, Herman Hollerith

invented the recording of data on a machine-readable medium. Earlier

uses of machine-readable media had been for control, not data. “After

some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards...”

[24] To process these punched cards he invented the tabulator, and the keypunch

machines. These three inventions were the foundation of the modern

information processing industry. Large-scale automated data processing

of punched cards was performed for the 1890 United States Census by Hollerith's company, which later became the core of IBM.

By the end of the 19th century a number of ideas and technologies, that

would later prove useful in the realization of practical computers, had

begun to appear: Boolean algebra, the vacuum tube (thermionic valve), punched cards and tape, and the teleprinter.

First general-purpose computers

The Zuse Z3, 1941, considered the world's first working programmable, fully automatic computing machine.

During the first half of the 20th century, many scientific computing needs were met by increasingly sophisticated analog computers, which used a direct mechanical or electrical model of the problem as a basis for computation. However, these were not programmable and generally lacked the versatility and accuracy of modern digital computers.

Alan Turing is widely regarded as the father of modern computer science. In 1936, Turing provided an influential formalization of the concept of the algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, providing a blueprint for the electronic digital computer.

[25] Of his role in the creation of the modern computer,

Time magazine in naming Turing one of the 100 most influential

people of the 20th century, states: “The fact remains that everyone who

taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program,

is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine.”

[25]

The ENIAC, which became operational in 1946, is considered to be the first general-purpose electronic computer. Programmers Betty Jean Jennings (left) and Fran Bilas (right) are depicted here operating the ENIAC's main control panel.

EDSAC was one of the first computers to implement the stored-program (von Neumann) architecture.

The first really functional computer was the Z1, originally created by Germany's Konrad Zuse

in his parents living room in 1936 to 1938, and it is considered to be

the first electro-mechanical binary programmable (modern) computer.

[26]

George Stibitz

is internationally recognized as a father of the modern digital

computer. While working at Bell Labs in November 1937, Stibitz invented

and built a relay-based calculator he dubbed the “Model K” (for “kitchen

table,” on which he had assembled it), which was the first to use binary circuits to perform an arithmetic operation. Later models added greater sophistication including complex arithmetic and programmability.

[27]

The Atanasoff–Berry Computer (ABC) was the world's first electronic digital computer, albeit not programmable.

[28] Atanasoff is considered to be one of the fathers of the computer.

[29] Conceived in 1937 by Iowa State College physics professor John Atanasoff, and built with the assistance of graduate student Clifford Berry,

[30]

the machine was not programmable, being designed only to solve systems

of linear equations. The computer did employ parallel computation. A 1973 court ruling in a patent dispute found that the patent for the 1946 ENIAC computer derived from the Atanasoff–Berry Computer.

The first program-controlled computer was invented by Konrad Zuse, who built the Z3, an electromechanical computing machine, in 1941.

[31] The first programmable electronic computer was the Colossus, built in 1943 by Tommy Flowers.

Key steps towards modern computers

A succession of steadily more powerful and flexible computing

devices were constructed in the 1930s and 1940s, gradually adding the

key features that are seen in modern computers. The use of digital

electronics (largely invented by Claude Shannon

in 1937) and more flexible programmability were vitally important

steps, but defining one point along this road as “the first digital

electronic computer” is difficult.

Shannon 1940 Notable achievements include:

- Konrad Zuse's electromechanical “Z machines.” The Z3 (1941) was the first working machine featuring binary arithmetic, including floating point arithmetic and a measure of programmability. In 1998 the Z3 was proved to be Turing complete, therefore being the world's first operational computer.[32] Thus, Zuse is often regarded as the inventor of the computer.[33][34][35][36]

- The non-programmable Atanasoff–Berry Computer (commenced in 1937, completed in 1941) which used vacuum tube based computation, binary numbers, and regenerative capacitor memory.

The use of regenerative memory allowed it to be much more compact than

its peers (being approximately the size of a large desk or workbench),

since intermediate results could be stored and then fed back into the

same set of computation elements.

- The secret British Colossus computers (1943),[37]

which had limited programmability but demonstrated that a device using

thousands of tubes could be reasonably reliable and electronically

re-programmable. It was used for breaking German wartime codes.

- The Harvard Mark I (1944), a large-scale electromechanical computer with limited programmability.[38]

- The U.S. Army's Ballistic Research Laboratory ENIAC (1946), which used decimal arithmetic and is sometimes called the first general purpose electronic computer (since Konrad Zuse's Z3 of 1941 used electromagnets instead of electronics). Initially, however, ENIAC had an architecture which required rewiring a plugboard to change its programming.

Stored-program architecture

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2012) |

Several developers of ENIAC, recognizing its flaws, came up with a

far more flexible and elegant design, which came to be known as the

“stored-program architecture” or von Neumann architecture. This design was first formally described by John von Neumann in the paper

First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC,

distributed in 1945. A number of projects to develop computers based on

the stored-program architecture commenced around this time, the first

of which was completed in 1948 at the University of Manchester in England, the Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM or “Baby”). The Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator

(EDSAC), completed a year after the SSEM at Cambridge University, was

the first practical, non-experimental implementation of the

stored-program design and was put to use immediately for research work

at the university. Shortly thereafter, the machine originally described

by von Neumann's paper—EDVAC—was completed but did not see full-time use for an additional two years.

Nearly all modern computers implement some form of the stored-program

architecture, making it the single trait by which the word “computer”

is now defined. While the technologies used in computers have changed

dramatically since the first electronic, general-purpose computers of

the 1940s, most still use the von Neumann architecture.

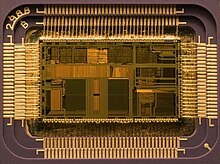

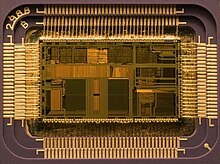

Die of an Intel 80486DX2 microprocessor (actual size: 12×6.75 mm) in its packaging

Beginning in the 1950s, Soviet scientists Sergei Sobolev and Nikolay Brusentsov conducted research on ternary computers, devices that operated on a base three numbering system of -1, 0, and 1 rather than the conventional binary numbering system upon which most computers are based. They designed the Setun, a functional ternary computer, at Moscow State University. The device was put into limited production in the Soviet Union, but supplanted by the more common binary architecture.

Semiconductors and microprocessors

Computers using vacuum tubes as their electronic elements were in use throughout the 1950s, but by the 1960s they had been largely replaced by transistor-based

machines, which were smaller, faster, cheaper to produce, required less

power, and were more reliable. The first transistorized computer was

demonstrated at the University of Manchester in 1953.

[39] In the 1970s, integrated circuit technology and the subsequent creation of microprocessors, such as the Intel 4004,

further decreased size and cost and further increased speed and

reliability of computers. By the late 1970s, many products such as video recorders contained dedicated computers called microcontrollers, and they started to appear as a replacement to mechanical controls in domestic appliances such as washing machines. The 1980s witnessed home computers

and the now ubiquitous personal computer. With the evolution of the

Internet, personal computers are becoming as common as the television

and the telephone in the household.

[citation needed]

Modern smartphones

are fully programmable computers in their own right, and as of 2009 may

well be the most common form of such computers in existence.

[citation needed]

Programs

Alan Turing was an influential computer scientist.

The defining feature of modern computers which distinguishes them from all other machines is that they can be programmed. That is to say that some type of instructions (the program) can be given to the computer, and it will process them. Modern computers based on the von Neumann architecture often have machine code in the form of an imperative programming language.

In practical terms, a computer program may be just a few instructions

or extend to many millions of instructions, as do the programs for word processors and web browsers for example. A typical modern computer can execute billions of instructions per second (gigaflops)

and rarely makes a mistake over many years of operation. Large computer

programs consisting of several million instructions may take teams of programmers years to write, and due to the complexity of the task almost certainly contain errors.

Stored program architecture

Main articles: Computer program and Computer programming

Replica of the Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM), the world's first stored-program computer, at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, England

This section applies to most common RAM machine-based computers.

In most cases, computer instructions are simple: add one number to

another, move some data from one location to another, send a message to

some external device, etc. These instructions are read from the

computer's memory and are generally carried out (executed)

in the order they were given. However, there are usually specialized

instructions to tell the computer to jump ahead or backwards to some

other place in the program and to carry on executing from there. These

are called “jump” instructions (or branches). Furthermore, jump instructions may be made to happen conditionally

so that different sequences of instructions may be used depending on

the result of some previous calculation or some external event. Many

computers directly support subroutines

by providing a type of jump that “remembers” the location it jumped

from and another instruction to return to the instruction following that

jump instruction.

Program execution might be likened to reading a book. While a person

will normally read each word and line in sequence, they may at times

jump back to an earlier place in the text or skip sections that are not

of interest. Similarly, a computer may sometimes go back and repeat the

instructions in some section of the program over and over again until

some internal condition is met. This is called the flow of control within the program and it is what allows the computer to perform tasks repeatedly without human intervention.

Comparatively, a person using a pocket calculator

can perform a basic arithmetic operation such as adding two numbers

with just a few button presses. But to add together all of the numbers

from 1 to 1,000 would take thousands of button presses and a lot of

time, with a near certainty of making a mistake. On the other hand, a

computer may be programmed to do this with just a few simple

instructions. For example:

mov No. 0, sum ; set sum to 0

mov No. 1, num ; set num to 1

loop: add num, sum ; add num to sum

add No. 1, num ; add 1 to num

cmp num, #1000 ; compare num to 1000

ble loop ; if num <= 1000, go back to 'loop'

halt ; end of program. stop running

Once told to run this program, the computer will perform the

repetitive addition task without further human intervention. It will

almost never make a mistake and a modern PC can complete the task in

about a millionth of a second.

[40]

Bugs

Main article: Software bug

The actual first computer bug, a moth found trapped on a relay of the Harvard Mark II computer

Errors in computer programs are called “bugs.”

They may be benign and not affect the usefulness of the program, or

have only subtle effects. But in some cases, they may cause the program

or the entire system to “hang,” becoming unresponsive to input such as mouse clicks or keystrokes, to completely fail, or to crash. Otherwise benign bugs may sometimes be harnessed for malicious intent by an unscrupulous user writing an exploit,

code designed to take advantage of a bug and disrupt a computer's

proper execution. Bugs are usually not the fault of the computer. Since

computers merely execute the instructions they are given, bugs are

nearly always the result of programmer error or an oversight made in the

program's design.

[41]

Admiral Grace Hopper, an American computer scientist and developer of the first compiler, is credited for having first used the term “bugs” in computing after a dead moth was found shorting a relay in the Harvard Mark II computer in September 1947.

[42]

Machine code

In most computers, individual instructions are stored as machine code with each instruction being given a unique number (its operation code or opcode

for short). The command to add two numbers together would have one

opcode, the command to multiply them would have a different opcode and

so on. The simplest computers are able to perform any of a handful of

different instructions; the more complex computers have several hundred

to choose from, each with a unique numerical code. Since the computer's

memory is able to store numbers, it can also store the instruction

codes. This leads to the important fact that entire programs (which are

just lists of these instructions) can be represented as lists of numbers

and can themselves be manipulated inside the computer in the same way

as numeric data. The fundamental concept of storing programs in the

computer's memory alongside the data they operate on is the crux of the

von Neumann, or stored program, architecture. In some cases, a computer

might store some or all of its program in memory that is kept separate

from the data it operates on. This is called the Harvard architecture after the Harvard Mark I computer. Modern von Neumann computers display some traits of the Harvard architecture in their designs, such as in CPU caches.

While it is possible to write computer programs as long lists of numbers (machine language) and while this technique was used with many early computers,

[43]

it is extremely tedious and potentially error-prone to do so in

practice, especially for complicated programs. Instead, each basic

instruction can be given a short name that is indicative of its function

and easy to remember – a mnemonic such as ADD, SUB, MULT or JUMP. These mnemonics are collectively known as a computer's assembly language.

Converting programs written in assembly language into something the

computer can actually understand (machine language) is usually done by a

computer program called an assembler.

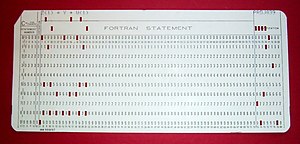

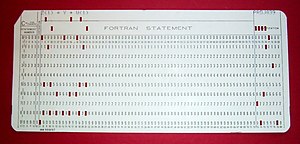

A 1970s punched card containing one line from a FORTRAN program. The card reads: “Z(1) = Y + W(1)” and is labeled “PROJ039” for identification purposes.

Programming language

Main article: Programming language

Programming languages provide various ways of specifying programs for computers to run. Unlike natural languages,

programming languages are designed to permit no ambiguity and to be

concise. They are purely written languages and are often difficult to

read aloud. They are generally either translated into machine code by a compiler or an assembler before being run, or translated directly at run time by an interpreter. Sometimes programs are executed by a hybrid method of the two techniques.

Low-level languages

Main article: Low-level programming language

Machine languages and the assembly languages that represent them (collectively termed

low-level programming languages) tend to be unique to a particular type of computer. For instance, an ARM architecture computer (such as may be found in a PDA or a hand-held videogame) cannot understand the machine language of an Intel Pentium or the AMD Athlon 64 computer that might be in a PC.

[44]

Higher-level languages

Main article: High-level programming language

Though considerably easier than in machine language, writing long

programs in assembly language is often difficult and is also error

prone. Therefore, most practical programs are written in more abstract high-level programming languages that are able to express the needs of the programmer

more conveniently (and thereby help reduce programmer error). High

level languages are usually “compiled” into machine language (or

sometimes into assembly language and then into machine language) using

another computer program called a compiler.

[45]

High level languages are less related to the workings of the target

computer than assembly language, and more related to the language and

structure of the problem(s) to be solved by the final program. It is

therefore often possible to use different compilers to translate the

same high level language program into the machine language of many

different types of computer. This is part of the means by which software

like video games may be made available for different computer

architectures such as personal computers and various video game consoles.

Program design

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2012) |

Program design of small programs is relatively simple and involves

the analysis of the problem, collection of inputs, using the programming

constructs within languages, devising or using established procedures

and algorithms, providing data for output devices and solutions to the

problem as applicable. As problems become larger and more complex,

features such as subprograms, modules, formal documentation, and new

paradigms such as object-oriented programming are encountered. Large

programs involving thousands of line of code and more require formal

software methodologies. The task of developing large software

systems presents a significant intellectual challenge. Producing

software with an acceptably high reliability within a predictable

schedule and budget has historically been difficult; the academic and

professional discipline of software engineering concentrates specifically on this challenge.

Components

Main articles: Central processing unit and Microprocessor

A general purpose computer has four main components: the arithmetic logic unit (ALU), the control unit, the memory, and the input and output devices (collectively termed I/O). These parts are interconnected by buses, often made of groups of wires.

Inside each of these parts are thousands to trillions of small electrical circuits which can be turned off or on by means of an electronic switch. Each circuit represents a bit

(binary digit) of information so that when the circuit is on it

represents a “1”, and when off it represents a “0” (in positive logic

representation). The circuits are arranged in logic gates so that one or more of the circuits may control the state of one or more of the other circuits.

The control unit, ALU, registers, and basic I/O (and often other

hardware closely linked with these) are collectively known as a central processing unit

(CPU). Early CPUs were composed of many separate components but since

the mid-1970s CPUs have typically been constructed on a single integrated circuit called a

microprocessor.

Control unit

Main articles: CPU design and Control unit

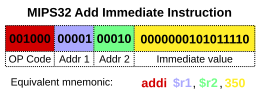

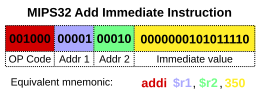

Diagram showing how a particular MIPS architecture instruction would be decoded by the control system.

The control unit (often called a control system or central

controller) manages the computer's various components; it reads and

interprets (decodes) the program instructions, transforming them into a

series of control signals which activate other parts of the computer.

[46] Control systems in advanced computers may change the order of some instructions so as to improve performance.

A key component common to all CPUs is the program counter, a special memory cell (a register) that keeps track of which location in memory the next instruction is to be read from.

[47]

The control system's function is as follows—note that this is a

simplified description, and some of these steps may be performed

concurrently or in a different order depending on the type of CPU:

- Read the code for the next instruction from the cell indicated by the program counter.

- Decode the numerical code for the instruction into a set of commands or signals for each of the other systems.

- Increment the program counter so it points to the next instruction.

- Read whatever data the instruction requires from cells in memory (or

perhaps from an input device). The location of this required data is

typically stored within the instruction code.

- Provide the necessary data to an ALU or register.

- If the instruction requires an ALU or specialized hardware to

complete, instruct the hardware to perform the requested operation.

- Write the result from the ALU back to a memory location or to a register or perhaps an output device.

- Jump back to step (1).

Since the program counter is (conceptually) just another set of

memory cells, it can be changed by calculations done in the ALU. Adding

100 to the program counter would cause the next instruction to be read

from a place 100 locations further down the program. Instructions that

modify the program counter are often known as “jumps” and allow for

loops (instructions that are repeated by the computer) and often

conditional instruction execution (both examples of control flow).

The sequence of operations that the control unit goes through to

process an instruction is in itself like a short computer program, and

indeed, in some more complex CPU designs, there is another yet smaller

computer called a microsequencer, which runs a microcode program that causes all of these events to happen.

Arithmetic logic unit (ALU)

Main article: Arithmetic logic unit

The ALU is capable of performing two classes of operations: arithmetic and logic.

[48]

The set of arithmetic operations that a particular ALU supports may

be limited to addition and subtraction, or might include multiplication,

division, trigonometry functions such as sine, cosine, etc., and square roots. Some can only operate on whole numbers (integers) whilst others use floating point to represent real numbers,

albeit with limited precision. However, any computer that is capable of

performing just the simplest operations can be programmed to break down

the more complex operations into simple steps that it can perform.

Therefore, any computer can be programmed to perform any arithmetic

operation—although it will take more time to do so if its ALU does not

directly support the operation. An ALU may also compare numbers and

return boolean truth values (true or false) depending on whether one is equal to, greater than or less than the other (“is 64 greater than 65?”).

Logic operations involve Boolean logic: AND, OR, XOR and NOT. These can be useful for creating complicated conditional statements and processing boolean logic.

Superscalar computers may contain multiple ALUs, allowing them to process several instructions simultaneously.

[49] Graphics processors and computers with SIMD and MIMD features often contain ALUs that can perform arithmetic on vectors and matrices.

Memory

Main article: Computer data storage

Magnetic core memory was the computer memory of choice throughout the 1960s, until it was replaced by semiconductor memory.

A computer's memory can be viewed as a list of cells into which

numbers can be placed or read. Each cell has a numbered “address” and

can store a single number. The computer can be instructed to “put the

number 123 into the cell numbered 1357” or to “add the number that is in

cell 1357 to the number that is in cell 2468 and put the answer into

cell 1595.” The information stored in memory may represent practically

anything. Letters, numbers, even computer instructions can be placed

into memory with equal ease. Since the CPU does not differentiate

between different types of information, it is the software's

responsibility to give significance to what the memory sees as nothing

but a series of numbers.

In almost all modern computers, each memory cell is set up to store binary numbers in groups of eight bits (called a byte).

Each byte is able to represent 256 different numbers (2^8 = 256);

either from 0 to 255 or −128 to +127. To store larger numbers, several

consecutive bytes may be used (typically, two, four or eight). When

negative numbers are required, they are usually stored in two's complement

notation. Other arrangements are possible, but are usually not seen

outside of specialized applications or historical contexts. A computer

can store any kind of information in memory if it can be represented

numerically. Modern computers have billions or even trillions of bytes

of memory.

The CPU contains a special set of memory cells called registers

that can be read and written to much more rapidly than the main memory

area. There are typically between two and one hundred registers

depending on the type of CPU. Registers are used for the most frequently

needed data items to avoid having to access main memory every time data

is needed. As data is constantly being worked on, reducing the need to

access main memory (which is often slow compared to the ALU and control

units) greatly increases the computer's speed.

Computer main memory comes in two principal varieties: random-access memory or RAM and read-only memory

or ROM. RAM can be read and written to anytime the CPU commands it, but

ROM is preloaded with data and software that never changes, therefore

the CPU can only read from it. ROM is typically used to store the

computer's initial start-up instructions. In general, the contents of

RAM are erased when the power to the computer is turned off, but ROM

retains its data indefinitely. In a PC, the ROM contains a specialized

program called the BIOS that orchestrates loading the computer's operating system from the hard disk drive into RAM whenever the computer is turned on or reset. In embedded computers,

which frequently do not have disk drives, all of the required software

may be stored in ROM. Software stored in ROM is often called firmware, because it is notionally more like hardware than software. Flash memory

blurs the distinction between ROM and RAM, as it retains its data when

turned off but is also rewritable. It is typically much slower than

conventional ROM and RAM however, so its use is restricted to

applications where high speed is unnecessary.

[50]

In more sophisticated computers there may be one or more RAM cache memories,

which are slower than registers but faster than main memory. Generally

computers with this sort of cache are designed to move frequently needed

data into the cache automatically, often without the need for any

intervention on the programmer's part.

Input/output (I/O)

Main article: Input/output

Hard disk drives are common storage devices used with computers.

I/O is the means by which a computer exchanges information with the outside world.

[51] Devices that provide input or output to the computer are called peripherals.

[52] On a typical personal computer, peripherals include input devices like the keyboard and mouse, and output devices such as the display and printer. Hard disk drives, floppy disk drives and optical disc drives serve as both input and output devices. Computer networking is another form of I/O.

I/O devices are often complex computers in their own right, with their own CPU and memory. A graphics processing unit might contain fifty or more tiny computers that perform the calculations necessary to display 3D graphics.

[citation needed] Modern desktop computers contain many smaller computers that assist the main CPU in performing I/O.

Multitasking

Main article: Computer multitasking

While a computer may be viewed as running one gigantic program stored

in its main memory, in some systems it is necessary to give the

appearance of running several programs simultaneously. This is achieved

by multitasking i.e. having the computer switch rapidly between running

each program in turn.

[53]

One means by which this is done is with a special signal called an interrupt,

which can periodically cause the computer to stop executing

instructions where it was and do something else instead. By remembering

where it was executing prior to the interrupt, the computer can return

to that task later. If several programs are running “at the same time,”

then the interrupt generator might be causing several hundred interrupts

per second, causing a program switch each time. Since modern computers

typically execute instructions several orders of magnitude faster than

human perception, it may appear that many programs are running at the

same time even though only one is ever executing in any given instant.

This method of multitasking is sometimes termed “time-sharing” since

each program is allocated a “slice” of time in turn.

[54]

Before the era of cheap computers, the principal use for multitasking was to allow many people to share the same computer.

Seemingly, multitasking would cause a computer that is switching

between several programs to run more slowly, in direct proportion to the

number of programs it is running, but most programs spend much of their

time waiting for slow input/output devices to complete their tasks. If a

program is waiting for the user to click on the mouse or press a key on

the keyboard, then it will not take a “time slice” until the event it

is waiting for has occurred. This frees up time for other programs to

execute so that many programs may be run simultaneously without

unacceptable speed loss.

Multiprocessing

Main article: Multiprocessing

Cray designed many supercomputers that used multiprocessing heavily.

Some computers are designed to distribute their work across several

CPUs in a multiprocessing configuration, a technique once employed only

in large and powerful machines such as supercomputers, mainframe computers and servers. Multiprocessor and multi-core

(multiple CPUs on a single integrated circuit) personal and laptop

computers are now widely available, and are being increasingly used in

lower-end markets as a result.

Supercomputers in particular often have highly unique architectures

that differ significantly from the basic stored-program architecture and

from general purpose computers.

[55]

They often feature thousands of CPUs, customized high-speed

interconnects, and specialized computing hardware. Such designs tend to

be useful only for specialized tasks due to the large scale of program

organization required to successfully utilize most of the available

resources at once. Supercomputers usually see usage in large-scale simulation, graphics rendering, and cryptography applications, as well as with other so-called “embarrassingly parallel” tasks.

Networking and the Internet

Main articles: Computer networking and Internet

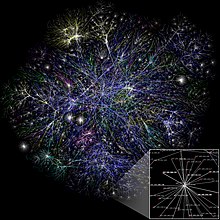

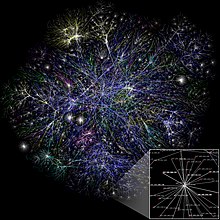

Visualization of a portion of the routes on the Internet.

Computers have been used to coordinate information between multiple locations since the 1950s. The U.S. military's SAGE system was the first large-scale example of such a system, which led to a number of special-purpose commercial systems such as Sabre.

[56]

In the 1970s, computer engineers at research institutions throughout

the United States began to link their computers together using

telecommunications technology. The effort was funded by ARPA (now DARPA), and the computer network that resulted was called the ARPANET.

[57] The technologies that made the Arpanet possible spread and evolved.

In time, the network spread beyond academic and military institutions

and became known as the Internet. The emergence of networking involved a

redefinition of the nature and boundaries of the computer. Computer

operating systems and applications were modified to include the ability

to define and access the resources of other computers on the network,

such as peripheral devices, stored information, and the like, as

extensions of the resources of an individual computer. Initially these

facilities were available primarily to people working in high-tech

environments, but in the 1990s the spread of applications like e-mail

and the World Wide Web, combined with the development of cheap, fast networking technologies like Ethernet and ADSL

saw computer networking become almost ubiquitous. In fact, the number

of computers that are networked is growing phenomenally. A very large

proportion of personal computers regularly connect to the Internet to

communicate and receive information. “Wireless” networking, often

utilizing mobile phone networks, has meant networking is becoming

increasingly ubiquitous even in mobile computing environments.

Computer architecture paradigms

There are many types of computer architectures:

- Quantum computer vs Chemical computer

- Scalar processor vs Vector processor

- Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) computers

- Register machine vs Stack machine

- Harvard architecture vs von Neumann architecture

- Cellular architecture

The quantum computer architecture holds the most promise to revolutionize computing.

[58]

Logic gates are a common abstraction which can apply to most of the above digital or analog paradigms.

The ability to store and execute lists of instructions called programs makes computers extremely versatile, distinguishing them from calculators. The Church–Turing thesis is a mathematical statement of this versatility: any computer with a minimum capability (being Turing-complete) is, in principle, capable of performing the same tasks that any other computer can perform. Therefore any type of computer (netbook, supercomputer, cellular automaton, etc.) is able to perform the same computational tasks, given enough time and storage capacity.

Misconceptions

Main articles: Human computer and Harvard Computers

Women as

computers in NACA High Speed Flight Station "Computer Room"

A computer does not need to be electronic, nor even have a processor, nor RAM, nor even a hard disk. While popular usage of the word “computer” is synonymous with a personal electronic computer, the modern

[59] definition of a computer is literally “

A device that computes,

especially a programmable [usually] electronic machine that performs

high-speed mathematical or logical operations or that assembles, stores,

correlates, or otherwise processes information.”

[60] Any device which

processes information qualifies as a computer, especially if the processing is purposeful.

Required technology

Main article: Unconventional computing

Historically, computers evolved from mechanical computers and eventually from vacuum tubes to transistors. However, conceptually computational systems as flexible as a personal computer can be built out of almost anything. For example, a computer can be made out of billiard balls (billiard ball computer); an often quoted example.

[citation needed] More realistically, modern computers are made out of transistors made of photolithographed semiconductors.

There is active research to make computers out of many promising new types of technology, such as optical computers, DNA computers, neural computers, and quantum computers. Most computers are universal, and are able to calculate any computable function,

and are limited only by their memory capacity and operating speed.

However different designs of computers can give very different

performance for particular problems; for example quantum computers can

potentially break some modern encryption algorithms (by quantum factoring) very quickly.

Further topics

Artificial intelligence

A computer will solve problems in exactly the way it is programmed

to, without regard to efficiency, alternative solutions, possible

shortcuts, or possible errors in the code. Computer programs that learn

and adapt are part of the emerging field of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Hardware

Main articles: Computer hardware and Personal computer hardware

The term

hardware covers all of those parts of a computer that

are tangible objects. Circuits, displays, power supplies, cables,

keyboards, printers and mice are all hardware.

History of computing hardware

Main article: History of computing hardware

| First generation (mechanical/electromechanical) |

Calculators |

Pascal's calculator, Arithmometer, Difference engine |

| Programmable devices |

Jacquard loom, Analytical engine, Harvard Mark I, Z3 |

| Second generation (vacuum tubes) |

Calculators |

Atanasoff–Berry Computer, IBM 604, UNIVAC 60, UNIVAC 120 |

| Programmable devices |

Colossus, ENIAC, Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine, EDSAC, Manchester Mark 1, Ferranti Pegasus, Ferranti Mercury, CSIRAC, EDVAC, UNIVAC I, IBM 701, IBM 702, IBM 650, Z22 |

| Third generation (discrete transistors and SSI, MSI, LSI integrated circuits) |

Mainframes |

IBM 7090, IBM 7080, IBM System/360, BUNCH |

| Minicomputer |

PDP-8, PDP-11, IBM System/32, IBM System/36 |

| Fourth generation (VLSI integrated circuits) |

Minicomputer |

VAX, IBM System i |

| 4-bit microcomputer |

Intel 4004, Intel 4040 |

| 8-bit microcomputer |

Intel 8008, Intel 8080, Motorola 6800, Motorola 6809, MOS Technology 6502, Zilog Z80 |

| 16-bit microcomputer |

Intel 8088, Zilog Z8000, WDC 65816/65802 |

| 32-bit microcomputer |

Intel 80386, Pentium, Motorola 68000, ARM architecture |

| 64-bit microcomputer[61] |

Alpha, MIPS, PA-RISC, PowerPC, SPARC, x86-64 |

| Embedded computer |

Intel 8048, Intel 8051 |

| Personal computer |

Desktop computer, Home computer, Laptop computer, Personal digital assistant (PDA), Portable computer, Tablet PC, Wearable computer |

| Theoretical/experimental |

Quantum computer, Chemical computer, DNA computing, Optical computer, Spintronics based computer |

Other hardware topics

| Peripheral device (input/output) |

Input |

Mouse, keyboard, joystick, image scanner, webcam, graphics tablet, microphone |

| Output |

Monitor, printer, loudspeaker |

| Both |

Floppy disk drive, hard disk drive, optical disc drive, teleprinter |

| Computer busses |

Short range |

RS-232, SCSI, PCI, USB |

| Long range (computer networking) |

Ethernet, ATM, FDDI |

Software

Main article: Computer software

Software refers to parts of the computer which do not have a

material form, such as programs, data, protocols, etc. When software is

stored in hardware that cannot easily be modified (such as BIOS ROM in an IBM PC compatible), it is sometimes called “firmware.”

| Operating system |

Unix and BSD |

UNIX System V, IBM AIX, HP-UX, Solaris (SunOS), IRIX, List of BSD operating systems |

| GNU/Linux |

List of Linux distributions, Comparison of Linux distributions |

| Microsoft Windows |

Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows NT, Windows 2000, Windows Me, Windows XP, Windows Vista, Windows 7, Windows 8 |

| DOS |

86-DOS (QDOS), IBM PC DOS, MS-DOS, DR-DOS, FreeDOS |

| Mac OS |

Mac OS classic, Mac OS X |

| Embedded and real-time |

List of embedded operating systems |

| Experimental |

Amoeba, Oberon/Bluebottle, Plan 9 from Bell Labs |

| Library |

Multimedia |

DirectX, OpenGL, OpenAL |

| Programming library |

C standard library, Standard Template Library |

| Data |

Protocol |

TCP/IP, Kermit, FTP, HTTP, SMTP |

| File format |

HTML, XML, JPEG, MPEG, PNG |

| User interface |

Graphical user interface (WIMP) |

Microsoft Windows, GNOME, KDE, QNX Photon, CDE, GEM, Aqua |

| Text-based user interface |

Command-line interface, Text user interface |

| Application |

Office suite |

Word processing, Desktop publishing, Presentation program, Database management system, Scheduling & Time management, Spreadsheet, Accounting software |

| Internet Access |

Browser, E-mail client, Web server, Mail transfer agent, Instant messaging |

| Design and manufacturing |

Computer-aided design, Computer-aided manufacturing, Plant management, Robotic manufacturing, Supply chain management |

| Graphics |

Raster graphics editor, Vector graphics editor, 3D modeler, Animation editor, 3D computer graphics, Video editing, Image processing |

| Audio |

Digital audio editor, Audio playback, Mixing, Audio synthesis, Computer music |

| Software engineering |

Compiler, Assembler, Interpreter, Debugger, Text editor, Integrated development environment, Software performance analysis, Revision control, Software configuration management |

| Educational |

Edutainment, Educational game, Serious game, Flight simulator |

| Games |

Strategy, Arcade, Puzzle, Simulation, First-person shooter, Platform, Massively multiplayer, Interactive fiction |

| Misc |

Artificial intelligence, Antivirus software, Malware scanner, Installer/Package management systems, File manager |

Languages

There are thousands of different programming languages—some intended

to be general purpose, others useful only for highly specialized

applications.

Programming languages

| Lists of programming languages |

Timeline of programming languages, List of programming languages by category, Generational list of programming languages, List of programming languages, Non-English-based programming languages |

| Commonly used assembly languages |

ARM, MIPS, x86 |

| Commonly used high-level programming languages |

Ada, BASIC, C, C++, C#, COBOL, Fortran, Java, Lisp, Pascal, Object Pascal |

| Commonly used scripting languages |

Bourne script, JavaScript, Python, Ruby, PHP, Perl |

Professions and organizations

As the use of computers has spread throughout society, there are an increasing number of careers involving computers.

Computer-related professions

| Hardware-related |

Electrical engineering, Electronic engineering, Computer engineering, Telecommunications engineering, Optical engineering, Nanoengineering |

| Software-related |

Computer science, Computer engineering, Desktop publishing, Human–computer interaction, Information technology, Information systems, Computational science, Software engineering, Video game industry, Web design |

The need for computers to work well together and to be able to

exchange information has spawned the need for many standards

organizations, clubs and societies of both a formal and informal nature.

Organizations

| Standards groups |

ANSI, IEC, IEEE, IETF, ISO, W3C |

| Professional societies |

ACM, AIS, IET, IFIP, BCS |

| Free/open source software groups |

Free Software Foundation, Mozilla Foundation, Apache Software Foundation |